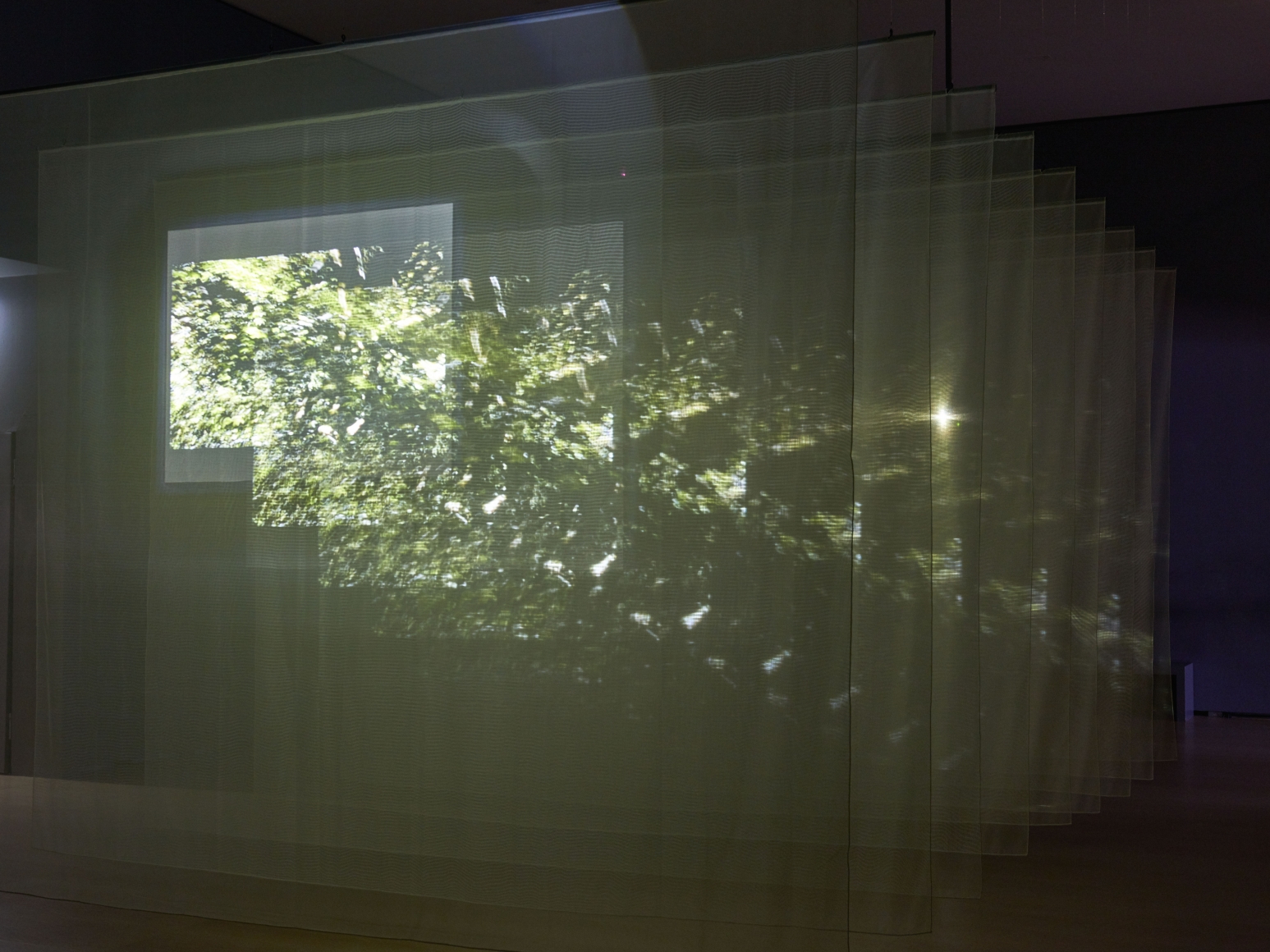

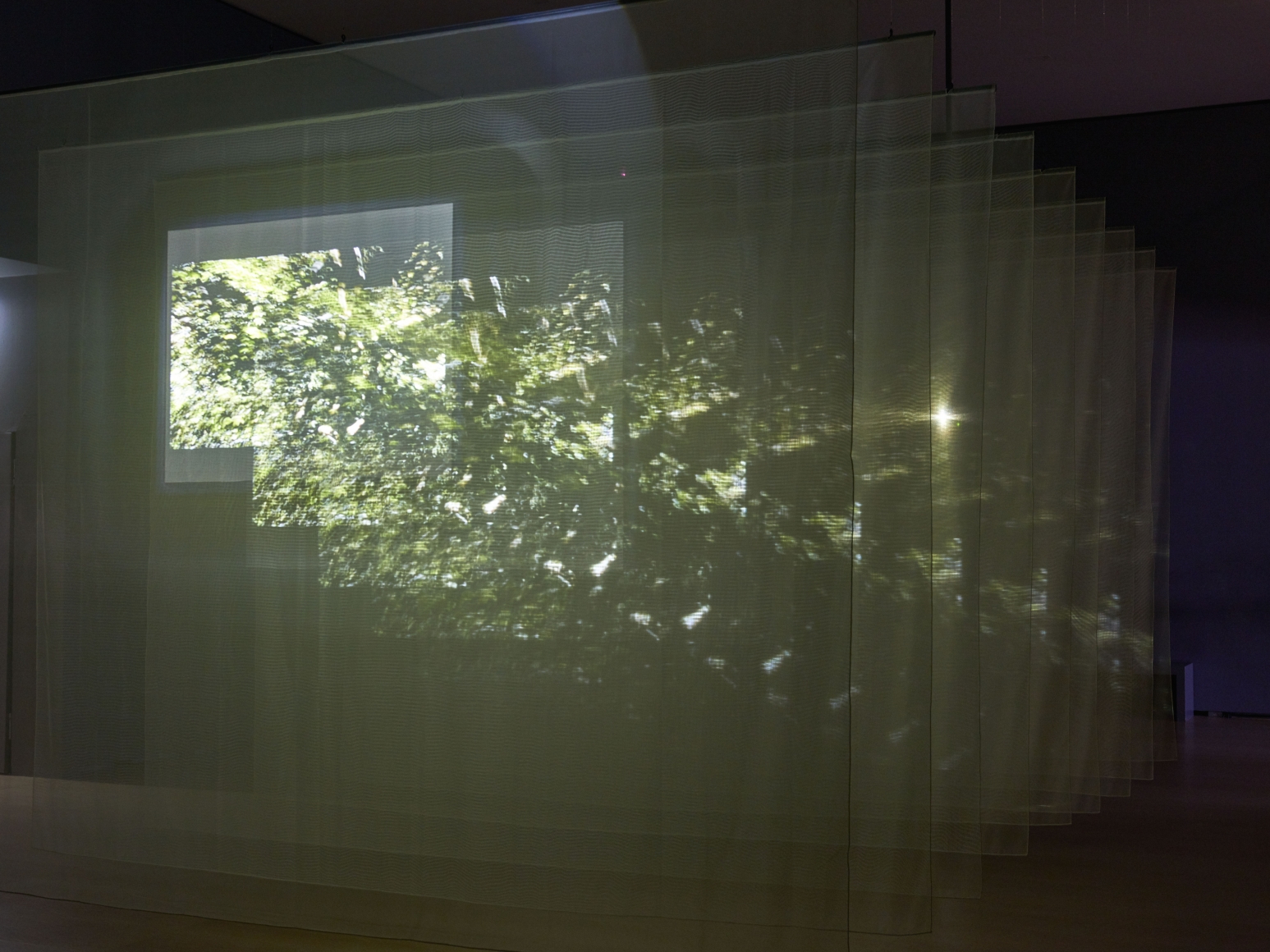

Central rotating screen, mirrored on one side; two channels of video projections at opposite ends of space, one color, one black-and-white, in large, dark room; amplified mono sound, one speaker; amplified mono sound, five speakers

ONLINE.ART.BLOG

Hito Steyerl is one of the artists that I have researched into for my project. I actually saw some of her works when I went to the Venice Biennale back in November 2019.

May You Live in Interesting Times, 58th Venice Biennale, May 11th – Nov 24th 2019

Power Plants, Serpentine Sackler Gallery, April 11th – May 6th 2019

Hello World―For the Post-Human Age, Art Tower Mito Japan, Feb 10th – May 6th 2018

How Not to Be Seen—a video by artist and critic Hito Steyerl—presents five lessons in invisibility. As titles that divide the video into distinct but interrelated sections, these lessons include how to: 1. Make something invisible for a camera, 2. Be invisible in plain sight, 3. Become invisible by becoming a picture, 4. Be invisible by disappearing, and 5. Become invisible by merging into a world made of pictures.1

This interest becomes visible not only in their performances, but also in their video work, photography, installations and drawings. Theater has been an important factor in Breure & Van Hulzen’s work from the very start. In 2017 they began making sculptures – assemblages in the form of human figures, but also separate heads in ceramics. Observations of daily life tend to form the point of departure for Breure & Van Hulzen’s works. The basis for their first sculptures was the notion that people are, in essence, always playing a role. Such a role is accompanied by certain personality traits, a specific ‘mask’, an individual body language, and deliberately chosen attributes such as clothing. The sculptures are presented as representatives of certain ‘roles’. For example, the sculpture Rosa, 2018 on the right.

Twenty-one sculptures made of ceramics, bronze, concrete, steel, plaster, wood and textile. Laminate flooring, translucent curtains, security mirrors.

The installation is essentially about a theft crime that happened to a 68 year old woman at a store in Oldenzaal, the Netherlands on November 22nd 2016. The theft was recorded by a security camera but the police still could not solve the case. The Public Prosecution Service decided to air the footage on a TV crime show to ask the public for tips on the thief, but this backlashes when the footage is aired on a spin-off controversial website. This results in the woman’s address being known to the public and began the threats of the public. She commits suicide day of the broadcast where she calls to turn herself in to the police. In a statement the Prosecution Service laments the situation, but it does not consider itself accountable for ‘what happens on the internet’. A later response states that the Prosecution Service ‘has had a wake-up call with regard to privacy’ but does not intend to change its current policy regarding the recognizable showing of suspects.

I went to Amsterdam last year and saw Accidents waiting to Happen (2019) at the Stedelijk Museum. Unfortunately, I couldn’t watch the performance that came with the installation but I really like seeing the sculptures. They were all very unique and had a lot of character. The room did emanate a hospital setting because of how large and white the space was. But my favourite part of the work was the micro-cameras that were attached to the walls all around the room. They were connected to the multiple monitors that were in each corner of the room and played a live streaming of the people in the room. Some of the monitors were flipped upside down whilst others had a time delay and its hard to tell which camera connects to which channel. This gave the sense of surveillance over the viewer, and it was kind of confusing knowing that we were being filmed but not knowing from which direction.

I really liked this because the viewer becomes part of the work, and it was engaging in an almost frustrating kind of way. The concept that the artists were trying to achieve also worked well because the camera captures the viewers alongside the sculptures, having the two diverge.

A lot of Lozano-Hemmer’s work are interactive installations that require an engagement from the audience. Having a history of BA Science in Physical Chemistry, Hemmer uses his knowledge and skills to manipulate and use advanced technology in his work.

Presence and participation are important in a lot of his work because the work requires to be activated by the viewer. A lot of the work is defined by the viewer’s active engagement. His fuses architecture with performance art to create work that discusses society and human nature, for his immersive technological installations.

Mieke Bal (Heemstede, 1946), a cultural theorist and critic, has been Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences Professor. She is also a video artist, making experimental documentaries on migration and recently exploring fiction. Her interests range from biblical and classical antiquity to seventeenth-century and contemporary art, modern literature, feminism, and migratory culture.

Michelle Williams Gamaker (London, 1979) is a video and performance artist. Her work varies from single-frame portraits and installations to complex renderings of reality via documentary and fiction. The subtle and sublime potential of story-telling is at the root of her work.

The nature of the exhibition encourages the “audience’s consideration, contemplation and confrontation.”

Interactive Contemporary Art: Participation in Practice edited by Kathryn Brown pg19

The work comprises of a small seated auditorium, with headphones that plays a narrative speech to each individual viewer. The viewer watches a reflective circular screen in front of them which reveals itself to be a jellyfish tank. The narrator in the headset discusses about the longevity of a jellyfish. Regarding the simplicity of the jellyfish having a small and simple system, we are forced to contemplate on the fragility of human existence and to reflect on the fact that jellyfish will probably outlive humanity. We are forced to reflect on our impact on the the world and ecosystems in the small time that we have on this world. This conclusion is formed when the screen reveals another set of people through the glass/tank having the same experience (listening to the same narration) but in a different timeline, being compared to the jellyfish.

I like this work because its very clever, in the way that it uses other humans (viewer) as part of the work to make the comparison with the jellyfish. It confronts us to reflect on our temporary existence whilst exploring the role of the viewer. The viewer becomes part of the work. Not only do they become part of the work, but the confrontation is moving as it is with other humans that are currently the other part of the room. The installation works by making us confront other humans.

BOB at Serpentine Galleries

Ian Cheng is an American artist born in 1984, having graduating from University of California, Berkeley with a dual degree in cognitive science and art practice.

He is known for his live simulation that explore the capacity of living agents to deal with change. These ‘simulations’ are also known to be ‘virtual ecosystems’. The work has less of a focus on the technological aspect and instead, focuses on the how the work can self-evolve and adapt, just like an ecosystem would if any changes are applied to it. The simulation will change and adapt and progress as different factors interact with the work. “It is a format to deliberately exercise the feelings of confusion, anxiety, and cognitive dissonance that accompany the experience of unrelenting change. I wonder if it is possible to love these difficult feelings, because when you love something and there is an abundance of it, you can begin to play and compose with it.“

Most recently, he has developed BOB (Bag of Beliefs), an AI creature whose personality, body, and life story evolve across exhibitions, what Cheng calls “art with a nervous system.” He exhibited BOB at the Serpentine Gallery in 2018, a sentient artwork that was continuously growing and evolving at all times, with every interaction. A grid of monitors shows a limbo space within which an animation of a bright red, spiky serpentine creature slithers about. That’s the titular “BOB.” Depending on when you see the show, BOB will be longer or shorter, and have a greater or fewer number of heads, which branch, hydra-like, from its body, as it evolves in relation to different stimuli.

user story (power scan), 2016 – Acrylic box, 3M privacy film, C-Type photographic print, polyester and antistatic tapes, security screws

Size: 33 x 24.5 x 2.5 cm

Edition of 7