Sound Installation with 100 speakers, microphones, printed text and metal stands, 2017-18

Site Specific

ARTICLE: Shilpa Gupta: the artist bringing silenced poets back to life

ONLINE.ART.BLOG

Born in Mexico City in 1967

His career began as a political cartoonist and he continues to incorporate witty humor into his work. His work ranges from large-scale installations of simple objects from everyday life. Often suspending the objects in a such a precise arrangement, they become witty representations of diagrams, solar systems, words, buildings, and faces. These shifts in perception are not just visual but also cultural, as the artist draws out the social history of the objects featured in his sculptures, films, and performances.

In Controller of the Universe 2007, a collection of hand tools, saws and other cutting materials are suspended in a coordinated assembly to signify an explosion of a toolbox. Here, tools can be understood as symbols of humanity’s desire to shape and control the world, yet this purpose is ultimately subverted by the subjective ordering of the work’s components.

Once again, in Cosmic Thing 2002, an entire Volkswagen Beetle is dissembled and suspended in all of its parts. Whilst depicting an explosion of the car from within , it also an act of dissection. The pervasive and popular Beetle is revealed as an emblem of political ideology and the inescapable reach of global capital.

American sculptor born in 1941. Her work is usually wax paintings and poured latex sculptures.

Benglis started as an Abstract Expressionistic painter, inspired by the gestural style of the traditional paintings. However, she claims she to want to ‘redefine’ what painting means. This is how she began using different materials and mediums to mimic the gestural style of painting but within a sculptural body. Benglis is interested in capturing fluid and motion in her solid sculptors, playing and juxtaposing from the hard and the soft, the fluid and the solid state of matter. she allowed the process of making to dictate the shape of her finished works, wielding pliant matter that “can and will take its own form.”

Often working in series of knots, fans, lumps, and fountains, Benglis chooses unexpected materials, such as glitter, gold leaf, lead, and polyurethane. In her use of candy colors, glitter and other craft materials, she distanced herself from the serious, brooding color and macho materials used by her contemporaries. In doing so, she sought to question traditional gendered distinctions in art, above all the opposition between art and craft.

Benglis took inspiration from Jackson Pollock’s dripping methods in painting, but took to a new level, coming away from the 2D canvas of flat surfaces. She began pouring directly onto the floor, removing the use of the canvas. This had a feminine approach to the method that Pollock had first introduced. Rejecting vertical orientation—as well as canvas, stretcher, and brush—the “pours” push conventions of easel painting to the point of near collapse. Examples of her work that had this feminist approach are Fallen Painting (1968) and Contraband (1969). Both of these floor works had the essence of invoking “the depravity of the ‘fallen’ woman” or, from a feminist perspective, a “prone victim of phallic male desire”. (Jones, Amelia (1998). Body Art/Performing the Subject. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. pp. 96–97)

Also, being one of the few female artists of the 1960’s, Benglis was highly involved and interested in feminist art, challenging the male-dominant minimalist movement. She was highly intrigued by mediums that were uncorrupted by male artists at the time, and started working in videography and photography to produce art that favored the feminists.

She also used media interventions (such as a well known ad placed in Artforum in 1974, showing the artist nude with a dildo between her legs) to explore notions of power and gender relations. Benglis was initially refused an editorial space in Artforum before paying for an advertisement within the art magazine, of a full page photograph of herself in the nude, wearing glasses and holding a dildo between her legs.

I have been interested in Sound art recently and I’ve been researching artists that utilizes sound in their works. Sound is being stretched and continually explored as a physical material as well as a non-material medium. These are just some of the artists and artworks I have been interested in.

Siobhan Hapaska is an Irish artist born in 1963. Her practice is wide-ranging, often producing mixed-media installations and sculptures. Her use of media is unlimited working from natural materials such as trees, skulls and fur, merged with a diverse vocabulary of materials an unique objects, synthetic materials. Hapaska also often incorporates sound and light elements into her work. Not only is diversity and exclusivity evident in her large range of media use, but also in the types of work produced, being both figurative and abstract. Because of the nature of her work and the interesting assemblages of contrasting materials, the work holds a lot of history and becomes open to multiple readings, allowing the effortless movement between abstraction and figuration. Though her work can be representative and hyper realistic, the combination of materials allow the work for a more open ended interpretation, addressing themes of communication, interiority, subjugation versus domination, loneliness and hurt. Hapaska has mentioned that she prefers her work to be this open-ended, stating “I think some people get very uneasy when they can’t find immediate, concrete explanations. I like ideas that are adrift. When things are not absolutes they become more interesting, because it throws the responsibility back on you, to understand what you might be.” The relationship and duality created upon the work is enigmatic, in states of conflict, distress, desire or compassion. At times, her sculptures touch upon different belief systems, ideologies or faiths, but never in a way that is ultimately resolved or redeemed. Rather, we are given an insight into the combustibility of the human condition, with all its flaws and contradictions; tenderness and destructiveness.

Hapaska’s recent works includes a new material called ‘concrete cloth‘, which is a canvas permeated by concrete. Its original function is for immediate construction of emergency dwellings. Hapaska manipulates this material into biomorphic forms whilst drawing attention to the contemporary concerns of housing and refugees. In each of these new sculptures, there is a relationship between two elements, each is a resolution of conflict or a system of support.

Us, 2016 (Concrete cloth, fiberglass, two pack acrylic paint and lacquer, stainless steel, oak)

Mirza is best described as a composer, taking inspiration and influence from a wide range of themes such as science, culture and religion and forming multimedia immersive installations, kinetic and audio sculptures and performance collaborations. The composer role is seen when through his use and manipulation of readymades within his work. He takes found objects and explores how the objects that interact with each other to form sounds in the shape of kinetic sculptures. Cross Section of a Revolution, 2011 is an example of how he harness the electro-acoustic interference produced by the items, by displaying how the sound of the radio is interfered and disrupted by a simple energy-saving light bulb. He does this often in his work, where he combines numerous components together in installations and performances where the individual elements are placed in conversation with one another.

Another way he fulfills his role as a composer is when he brings in context and themes into his work. Mirza in the past, has drawn from his own cultural and religious experiences to produce work that explore into these through an audiovisual perspective. Taka Tak, 2008 is an amalgamation of work that explores the interaction and electro-acoustic interference readymade objects to his personal experience of his Pakistani and Islamic culture, through an assemblage of a video of a Pakistani street chef cooking, an interfered beat emitting from a Qu’ran stand, connected to a turntable weighed down with a Sufi statue and a transistor radio.

Mirza frequently combines sounds with LED lights in his work, playing with the idea of the combination of sound-waves and light-waves and exploring how we perceive the two together. Does the light represent the sound or vice versa? It draws attention to the line that distinguishes the both and explores that further. One example is the work A Chamber for Horwitz; Sonakinatography Transcriptions in Surround Sound, 2015 which is a collaboration with the artist Channa Horwitz. Taking Horwitz complicated graphical coloured drawings, he transforms the different colours into sound and light in the shape of a room. The drawings of Horwitz can be physically experienced and the distinction between light and sound are merged and undefined. This leads us to consider the categorization of noise and music and what we perceive to be the characteristic properties of these, and what can be manipulated to be seen as a characteristic of sound (such as light, or colour from Horwitz drawings). Another example is An_Infinato,2009 (a readymade assemblage of a piano keyboard, LED light circle and galvanised bin) which draws attention to the possibility of the visual and acoustic as one singular aesthetic form.

Ernesto Neto’s works explores constructions of social space and the natural world by inviting physical interaction and sensory experience. Though his works, usually site specific and interactive, lack a sense of context and generally considered minimalist, Neto’s large-scale sculptures and installations differ through the interactive and intense olfactory qualities. Neto comes from a generation of Brazilian artists in the 1950s and 60s that followed Neo-concretism, a movement that rejected the pure rationalist approach of concrete art and embraced a more phenomenological and less scientific art. Neo-concretism aims to disassemble the limitations of the object, merging art and life together which led to developments in participatory and immersive art. This is seen in Neto’s work as his tactile and biomorphic structures takes inspiration from the natural world and life and creates new environments that explores the boundaries of the physical and social space.

The range of media he uses vary from stretchy poly-amide textiles, nylon, styrofoams, knitted crochet, stockings and other textiles to create his heavily-physical interactive installations, Furthermore, his structures often draw the olfactory sense through the use and play of scents such as aromatic spices, candies and sand. He also plays a lot with the height and composition of the space, having netting separate and cut into the space, whilst pendulous sculptures hang from the ceiling. This playful construction of the environment makes viewers more spatially- aware and draw attention to the body within the space.

– Ernesto Neto

I like his work because it demands participation and interaction from its viewers. His work targets all senses, even with smells, using spices like cumin and turmeric etc. And he uses material very simply but in a way that completely changes the space. I would to see one of his large-scale installations up close one day, and to be able to interact with the work and play within the space that is created. Especially his bigger pieces that can be climbed upon and is suspended over the floor. Its like a giant playground for adults, meant to be enjoyed and experienced.

“When working with sound as a material or auditory abject, there are a great number of essential prerequisites to consider in order to deepen the intensity of the piece: What is it that makes found this sound more special or intense than that sound?”

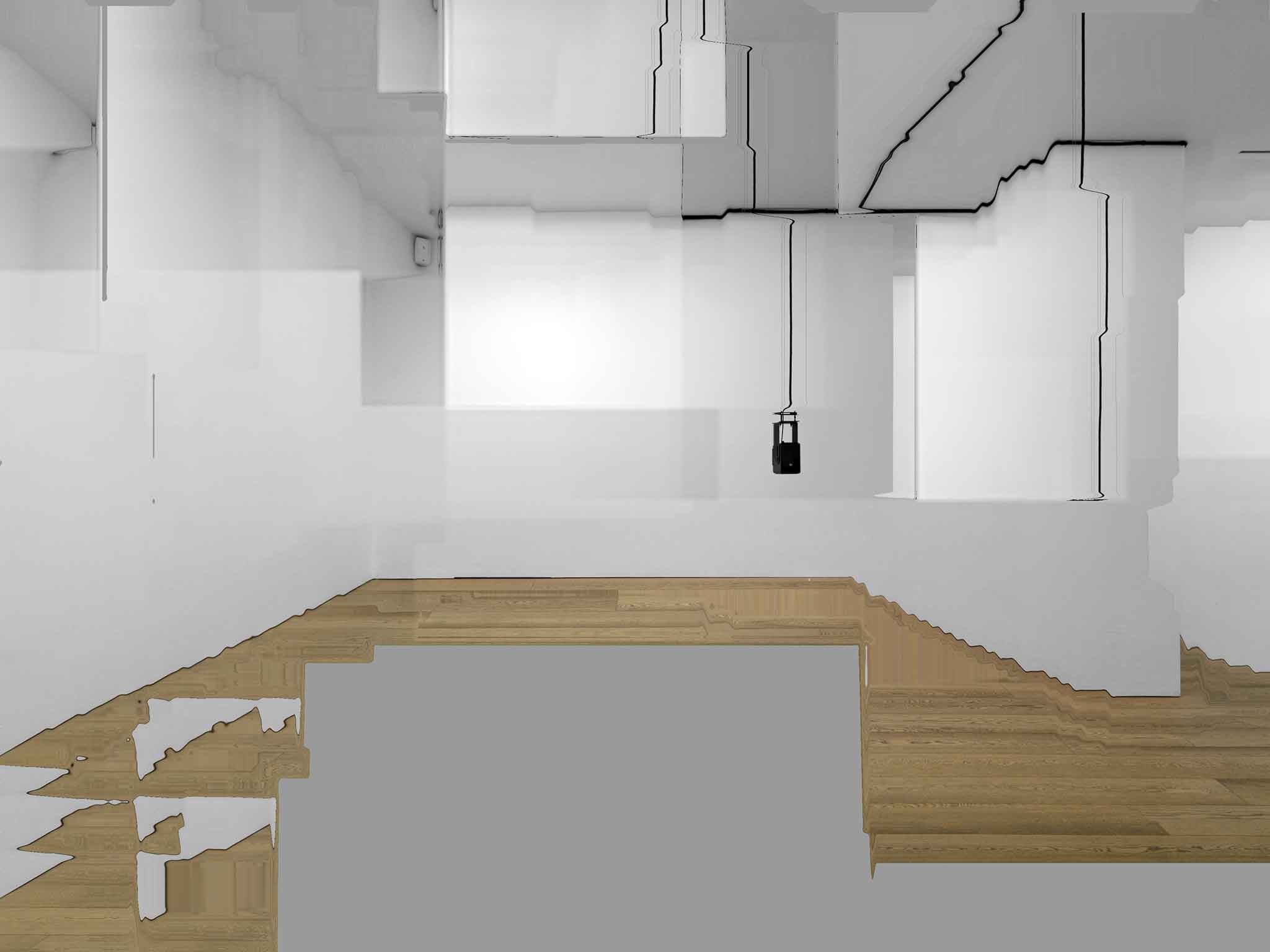

Florian Hecker was born in 1975 in Germany. He works with ‘synthetic sound, the listening process and the audience’s auditory experiences’.

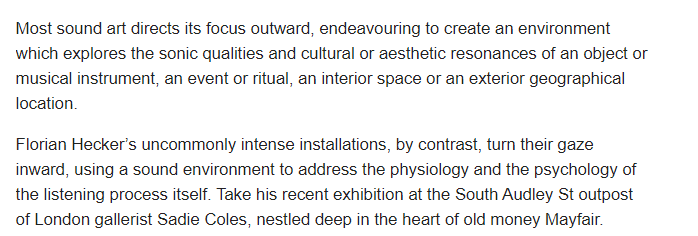

What I like about this work in particular in how Hecker explores how sound waves travel through the space and manipulates it to fill the gallery space. Using curved mirrors, the synthetic sounds are reflected and diverted around the room, ‘thus heightening the complexity of the sound installation’. He creates a sound/ space experience -‘constantly changing perceptions of space, the body and themselves’.

I like this work because it is hardly a visual piece of art. It depends highly on the audience’s experience and each experience is individualistic to the person because as the quote says above, every person experiences and hears sounds different to the other. His work emphasizes an active and subjective experience. This idea is further supported as sound is affected by the spatial composition, temperature (factors) of that specific day, making the work active and boundless.

Another example of how Hecker uses a sound environment to address the physiology and the psychology of the listening process itself, is the works Chimerization (2012) and Hinge (2012) which were exhibited together. Chimerization (3 readings of “experimental libretto” in 3 different languages) is played on tripling, doubling and echoes of the sounds. This tripling & doubling gives his work ‘linguistic dimensions‘ which allows him to explore how the audible sounds affects the spatial ‘to investigate the notion of psycho-acoustics‘. Once again, his work is not visually heavy but very focused on the acoustics and the experience.

Ear-witness Theatre/ Inventory (2018) at Chisenhale Gallery – Nominated for the Turner Prize 2019 alongside After Sfx (2018)– 95 objects ‘all derived from legal cases in which sonic evidence is contested and acoustic memories need to be retrieved‘ from ear witnesses description

‘How the experience and memory of acoustic violence is connected to the production of sound effects‘

Collapsing building = “like popcorn”, Gunshot =” somebody dropping a rack of trays”

Explores the ‘language of and between objects‘

I like this work because of the comparisons and the logical thinking that Lawrence Abu Hamdan has put into this work. For example, the fact that this is a representation of ear-witness evidence that has been collected and presented it in an archival ‘inventory’ way to further support that idea. I also like the visual objects of the audio description that the ear-witnesses describe and how it is displayed as an installation. So that we can link/ relate the objects to the sound described. It focuses and highlights on the language surrounding sounds/ audio and explores that ambiguity. Like how when describing a gunshot to a sound that we can relate to is “somebody dropping a rack of trays”. It juxtaposes from the violent act & audio of a gunshot when compared to a rack of trays. This theme of ear witnesses is applied to Saydnaya (2017) which is an audio investigation into the Syrian regime prison of Saydnaya. Its estimated that 13,000 people have been executed in Saydnaya since 2011 and the prisoners are kept in darkness, having only their hearing as their most relied sense, making up most of their memories & recollections of the place as audio memories. The work oscillates between the former prisoner’s testimonies and their reenacted whispers as sonic evidence. I think this work is important and valuable in telling the witnesses stories and revealing the harsh conditions of the prison as well as exploring the significance of sound / audio is. Art has predominantly been visual for all of its existence and though sound is just now getting recognition, I think people forgot how hearing/ sound/ audio plays a big part in our life. Saydnaya (2017) shows. how sometimes audio is better in recollecting/representing memories than visual imagery.

Another reason why I like Hamdan’s work is his activism & political (social) interest that he brings in. Like Earshot (2016) investigates the shooting of 2 Palestine teenagers by Israeli Soldiers in May 2014, that were denied and misconstrued by Israel media. Using art as a medium ‘a special techniques designed to visualize the sound frequencies‘, Hamdan found critical evidence valuable to the investigation and to bring justice to those who were immorally killed. Using sound as a medium and investigating it more, Hamdan questions ‘the ways in which rights are being heard today‘.